The notion of football played

‘the right way’ is simultaneously a conceptual scourge to be fought, and an essential safeguard against the sundry Pulises of the world who fear nothing more

than beauty. How do we reconcile our need for some kind of aesthetic thrill

from matches with the fact that the nature of this thrill will remain ever

elusive? What too of those players (or, more rarely, teams) whose commitment to

the stylish overwhelms their connection to the brute ‘reality’ of the game? Put

more simply: what space does fantasy occupy in football?

For reasons that should become

more apparent later, this debate can be framed very neatly through a brief

consideration the notion of the good will in the work of the fusty

Konigsberger, Immanuel Kant. Kant bases his ethics upon the notion of the good

will – a will elicited in line with pure practical reason as opposed to

pathological motivations founded upon material practical reason. For example,

one must refrain from theft because this is the right thing to do, rather than

from fear of punishment; fear of the hangman’s noose does not make one a good

man, for otherwise all cowards would be men of great virtue. But how can Kant

prove that these non-pathological acts exist? The elusive quality that allows

pure reason to be practical (hence not pathological) – termed the

‘philosopher’s stone’ by Kant – is crucial to his philosophy. And yet the only

way that Kant can get out of this apparent dead end is to appeals to das Faktum der Vernunft (the fact of reason),

although he himself admits that no example

can be offered to support his argument: ‘the moral law is given as a fact of

pure reason of which we are a priori

conscious, and which is apodictically certain, though it be granted that in

experience no example of its exact fulfilment can be found.’[1] As

such we are left with a moral law which is simply a Faktum that cannot be demonstrated. What we have is a supposed basic fact and an apodictic appeal to a

conception of morality which is binding from that point on. Barcelona offer perhaps the closest

approximation to this in today’s game. The basic fact that they play

football in the ‘right way’ is undemonstrable, yet noted moralist Silvio

Berlusconi recently advised his Milan side to go out against Juventus and ‘play

more like Barcelona’. Proof if proof be need be.

In his essay Kant avec Sade, unbearable obfuscator Jacques Lacan pointed out

that the line of inquiry suggested by Kant opens onto far more expansive

vistas:

[T]he Sadean

bedroom is of the same stature as those places from which the schools of

ancient philosophy borrowed their names: Academy, Lyceum, and Stoa. Here as

there, one paves the way for science by rectifying one’s ethical position, in

this respect, Sade did indeed begin the groundwork that was to progress for a

hundred years in the depths of taste in order for Freud’s path to be passable.

If Freud was able to enunciate his

pleasure principle without even having to worry about indicating what

distinguishes it from the function of pleasure in traditional ethics…we can

only credit this to the insinuating rise in the nineteenth century of the theme

of “delight in evil”. Sade represents here the first step of a subversion of

which Kant…represents the turning point.[2]

For Lacan, Kant is not honest

enough to realise the full consequences of his philosophy and this honesty is

better seen in the work of Sade. Kant’s arrival at an aporia when attempting to discern the good will from a pathological

will means that he is forced to rely on a notion of conscience, a supposed

‘voice within’ which looks suspiciously like a slight of hand or deux ex machina. Sade entertains no such

fanciful optimism. Lacan identifies the following maxim for jouissance within Sade, noting that it

relates to Kant’s own maxim insofar as it is enunciated as a universal law: “I

have the right to enjoy your body,” anyone can say to me, “and I will exercise

this right without any limit to the capriciousness of the exactions I may wish

to satiate with your body.”[3]

This maxim appeals to the Other rather than the ‘voice within’. Given that we

cannot possibly discern the good will, it is the will to jouissance which more perfectly expresses freedom.

|

| "I'll put a fag in my mouth, and think of Sade" |

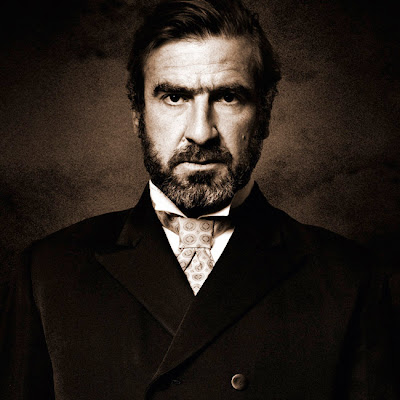

What then of footballing jouissance

and footballing good will? There are some who would claim that kung-fu

kicking a racist in the face is enough to elevate one above all future

criticism. For the duration of this piece, let’s pretend that I think

otherwise. Of course I am talking about Eric Cantona, a man habitually regarded

as the catalyst for Manchester United’s ascent towards the summit of world

football and one of the greatest players ever to have played in the Premier

League. But this is not what interests me about Cantona: whether Manchester

United sink or swim in the top flight is not really my interest. What is of

more interest is what Cantona brought out in the fans who so admired him,

rekindling a certain hope and bringing to the fore an appreciation of art in

addition to the artisan.

Cantona has a place in an

impressive lineage of Manchester United number 7s that also includes George

Best, Bryan Robson, David Beckham, Cristiano Rolando and @themichaelowen. All

of these rank amongst the best players in the history of the club (apart from

Owen), and all of them were winners (again apart from Owen). But Cantona

brought out something else in supporters. He was acknowledged as a winner, but

above this, he was recognised as an artist. For a striker, his record of 64

league goals in 143 games for Manchester United is hardly exceptional. The

starkest contrast is with his contemporary successor, Cristiano Ronaldo. CR7 is

a machine of a player, a statistic on steroids heading in locomotive fashion

towards success via the shortest, most economical route possible. Cantona was

not like that. Trailed by the seductive aroma of Gallic nonchalance, Eric

always seemed as if he was only partially focused on the win – he had other

considerations to pay heed to. Indeed Coupe du Monde winning coach Aime Jacquet

once said of Cantona: ‘Sometimes he lacks the killer instinct in front of goal.

There he is a poet, in love with the ball, seeking a gesture for its own sake.’

A criticism and a compliment in one, this encapsulates Cantona perfectly: a

great player, yes, but perhaps one too in love with what he perceives to be

beautiful to deliver the ugly, killing blow (the ‘Dirk Kuyt’, to coin a

phrase).

The conventional narrative, then,

might have us consider Cantona as something of a poet, if we take poetry to be

symbolic of decoration and artifice. Through poetry he escaped the idea of football

as solely orientated towards the win. It is a nice thought, but we could easily

look at this from another, less charitable angle. What if, rather than seeing

Cantona as endorsing art for art’s sake, we saw his perceived charity as a

handy deflection for a surplus of ego? Was the unnecessary pass to the teammate

an act of gratuitous good will or just an attempt to show how good he himself was?

Were Cantona’s acts those of egomania or florid poetry? In order to address

this question, it is useful to refer back to elucidate the role of fantasy in

ethics through the dynamic between Kant and Sade.

|

| Immanuel Kantona |

We have seen how by breaking down

the conventional dialectic between desire and Law – arguably reducing them to

one and the same thing – Kant clears the way for Sade. But I do not believe

that it is a failing of Kant to not go so far as to adopt a Sadean outlook. The

explanation for the difference in their respective philosophies can be

explained with reference to the respective fantasies invoked by Kant and Sade. In

both Kant and Sade an apparently indifferent nature is supplemented by a

second, ethical, nature: in Kant the kingdom of ends and in Sade the pursuit of

evil. The fact that their ethical edifices are supported by fantasy certainly

affects how they should be read.

In the work of Sade, enjoyment is

inhibited by the pleasure principle (the limit to what the body can endure)

since the body is not designed to go the full lengths of enjoyment such that

desire can be properly fulfilled. What Sade proposes is a fantasy of infinite

suffering, a suffering which can surpass the physical limits of the human body

in order to journey further still towards satisfying desire, even though that

desire will never be fully satisfied. The promise of eternal torture is the

fantasy which sustains the Sadean anti-ethical edifice. But there is an equal

and opposite movement within Kant’s ethical edifice, as Alenka Zupančič has

noted:

‘For Kant,

freedom is always susceptible to limitation, either by pleasure…or by the death

of the subject. What allows us to ‘jump over’ this hindrance, to continue to be

free beyond it, is what Lacan calls the fantasy. Kant’s postulate of the

immortality of the soul…implies precisely a fantasmatic ‘solution’… [I]f you

persist in following the categorical imperative, regardless of all pains and

tortures that may occur along the way, you may finally be granted the

possibility of ridding yourself even of the pleasure and pride that you took in

the sacrifice itself; thus you will finally reach you goal. Kant’s immortality

of the soul promises us then quite a peculiar heaven. For what awaits his

ethical subjects is a heavenly future that bears an uncanny resemblance to a

Sadean boudoir.’[4]

In short, Kantian ethics includes

the possibility of anti-ethics but for the thin veil of fantasy. Yet whilst Kant’s

fantasy at least aspires towards some idea of a good, Sade’s fantasy is one of

selfish depravity, blind to the notion of the good will and non-pathological

acts.

Returning to Cantona, then, we

can see the terms on which fans can interpret him as eliciting art for art’s

sake as opposed to indulging his own ego – or, exaggeratedly, why he is seen as

residing in the kingdom of ends as opposed to the Sadean boudoir. It must be

their fantasy that there is inherent value in aspiring towards the beautiful.

Within the framework discussed above, this is how we can distinguish Cantona’s

work from Sadean self-indulgence. That fans were willing to read Cantona as a

poet as opposed to an egomaniac speaks of the concealed poets within all

football fans who, whether or not they can enunciate it themselves, have an

idea of what they find admirable and desirable in the game, irrespective of the

result at the end of ninety minutes.

Of course this is only binding if

one accepts a rigidly Kantian/modern framework. Personally I would question

whether the mere fact that one enjoys something detracts at all from whether an

action is good or not. Here, perhaps, we would do well to consider Dennis

Bergkamp, a player who, like Cantona, was accused throughout his career of

lacking a killer streak. Bergkamp was not always looking to score: ‘I was

looking for that pass all the time, and the pleasure I got! It gave me so much

pleasure, like solving a puzzle. Scoring a goal is, of course, up there. It is

known. It’s like nothing else. But for me, in the end, giving the assist got

closer and closer to that feeling.’[5]

Cantona is more than a player,

for he is also a figure of fantasy. The way that he is remembered by football

fans speaks of the hope that poetry can shatter the prosaic, the pathological

and the mechanic; the hope that art can overcome ego. It is interesting how we

are unwilling to read others in the same way: Ballotelli’s insouciant back heel,

for example, was not considered art but rather petulance. Perhaps nowadays,

with a high quality domestic league and global televised football, we are no

longer looking for Eric (like the film!) to provide this reassurance. It is

telling that in France Cantona was regarded variously as ‘a pretentious country

boy, a roughish son of Marseilles, an idiot

savant.’[6] Who is

to say that if he walked amongst us today he would not be derided (much like

Plato’s returning escapee from the cave)? Somewhere in Cheshire, Dimitar

Berbatov sits alone, his retina burnt by the sun, wondering what would have

been if only his fans had fostered more fantasy.

|

| Burnt by the sun |

[1] Kant, Immanuel (2004) Critique of Practical Reason, Kingsmill Abbott, Thomas (trans.),

New York, Dover Publications, p.48.

[2] Jacques Lacan, ‘Kant With Sade’, in Ecrits The First Complete Edition in English,

trans. Bruce Fink (New York:

W. W. Norton & Company, 2006), p. 645.

[3]

Ibid, p.648.

[4] Alenka

Zupančič, ‘Kant with Don Juan and Sade’, in Joan Copjec (ed.), Radical Evil (London: Verso, 1996), pp. 120-121.

[5] For more

gems like this see David Winner’s

interview with Bergkamp in episode 1 of The

Blizzard.

[6] Ian

Ridley, ‘‘Oooh, Aaah, Cantona!’’, in Christov Ruhn (ed.), Le Foot (London: Abacus, 2000), p. 155.

No comments:

Post a Comment