Football in the GULag

We Never Make Mistakes

1 December 2011

7 November 2011

Manchester City: A Serious Club On Serious Earth

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad, you’re mad.’

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

Manchester United do not lose 6-1 at Old Trafford often. In a season of seminal results (no one is going to forget Arsenal’s silly breakdown at the Theatre of Dreams) this still stands out. It is the kind of result that may one day be looked back upon as marking a sea change – a result that marked that fateful point, when we finally started taking Serious Club Manchester City seriously.

Of course even before Johnny Evans (less a footballer than a verb, synonymous with ‘to fuck up’) tried and failed to do defending before exploding into the surface of the Death Star, Manchester City had had an impressive season. Ditching the ‘broken team’ concept that Mancini employed for most of last season (and at his time in charge of Inter) this year’s City have adopted a more holistic formation, with Agüero, Balotelli and Dzeko taking turns to provide star performances up front, and David Silva doing a fine impression of the best player in the world (just don’t tell Messi or Ronaldo). Even last season City were good enough to finish in the top four. In fact, ever since the disinterested Swede (Eriksson) took the City job and signed talents including Elano, Martin Petrov and Corluka – and certainly since they took to riding their sweet Sheik’s dollar – teams have regarded City as a decent side. But it would seem that for many involved with Manchester City this is not enough. Money can buy you success, but can it buy you seriousness?

The clamour for seriousness is a recent phenomenon at Manchester City. Historically the Citizens have never loitered far from pathos, nor bathos. Previous promises of success have left them stood disappointed, looking whimsically at the camera. This time, however, is the real deal, and the executives at City want to make sure that everyone realises this (which is odd, given how self-evident it is). Paramount for the board is projecting the air of a big club – a Serious Club. At the Champions League draw, the City delegation evoked the image of a dad behind the wheel, clearly lost but too proud to ask for directions: ‘Of course we’re at the Champions League draw. We’re just one big club amongst others here. Just a room full of big bitchin’ clubs.’ That this was City’s first appearance in the Champions League appeared to be something of a taboo subject. One can imagine former big cheese Gary Cook briefing the delegates beforehand, instructing them to play it cool and not embarrass themselves in front of the men from Madrid and Milan.

|

| Executive decision making with Patrick Viera |

Of course Garry Cook is something of a sensitive subject for Manchester City. He was, after all, forced to step down from his post after somewhat tasteless statements pertaining to Nedum Onuha’s mother (and her unfortunately amusing use of adjectives). Yet on reflection, Cook might have been the perfect man to be in charge of City. He, more than anyone, pushed the line of City’s newfound seriousness. Romping into the distance with attempts to sign Kaka, coordinating provocative marketing campaigns such as that which saw former United star Tevez plastered across billboards, and playing the lead role in the bizarre docudrama that accompanied the signing of Samir Nasri. Cook believed that City were big time, and he’d tell this to anyone who’d listen, and if they weren’t listening he’d make them.

Yet there was something else about Cook that made him the perfect front man for Manchester City. This second quality was, ironically, that which lost him his job: his blunderous propensity. The Cookie Monster’s long list of faux pas does not need to be recounted, it is so familiar. Apparently paradoxically, the person keenest to portray City as a serious club was the silliest thing about them. But on reflection, this was not paradoxical at all – rather it was entirely appropriate. As mentioned above, there has always been an element of pathos&bathos to City. How perfect, then, that their super slick CEO was also a bungling corporate loon. Perhaps, for those fans somewhat alienated by the takeover, this kind of a figure was a necessary piece of continuity with City’s past, a totemic clown linking the Manchester City of the past with the Manchester City of the future. Granted, Cook was cringe worthy, but isn’t the occasional cringe something that is part and parcel of being a Citizen? His dismissal was not just the termination of a contract – it was an attempted exorcism.

|

| Hey Brother - how's your mother? |

Without a figure such as Cook, how are City fans meant to relate to their club? The Cult of Seriousness is not limited to the club’s hierarchy – it is also evidenced on the terraces by an increasingly vocal lack of a sense of humour in certain sections of the support. There is also an increasing tendency to want things both ways – to be a big, serious club, but also to be able to play the underdog card. Indeed, City have spent almost their entire history in the shadow of Manchester United, a club that is undoubtedly amongst the biggest in the world; United were always the rich neighbours, buying their way to success. But now that it is City who are able to throw their cash around, one has to wonder whether the newfound tetchiness stems from a collective shame stemming from the adoption of United’s methods, of their capitulation to the culture of unsustainable spending that saw Chelsea reviled in the mid-2000s. This identity crisis at the heart of Manchester City means that supporters struggle to define their relationship with the club (and even more so their relationship with mercenary figures such as Tevez and his, frankly, disgusting salary and soul). In response some will find themselves alienated, but others will have to aggressively realign themselves with the club – a realignment towards the club’s new modus operandi: Seriousness.

The uncomfortable thing about the humourless attitude adopted by Manchester City (both as a club and amongst large groups of the supporters) is the inability to accept the novelty of their situation. Being a football fan can be a fairly thankless endeavour for extended amounts of time, with occasions for celebration few and far between. With the recent takeover, Manchester City have undergone a genuine revolution – a different beast to the Randy Lerner revolution at Villa or the John Henry revolution at Liverpool. In a short period of time, City have gone from relegation contenders under Stuart Pearce to Champions League potentials under Mancini. This is remarkable and one would think that City fans would recognise this, whether or not it betrays the fact that City is not a big European club in the same way as AC Milan or Real Madrid are. For in recognising this novelty, they might also manage to discern the fact that this surreal situation is not entirely extraneous to the pathos&bathos that had previously characterised the club. What, after all, is sillier than Manchester City bringing in top players such as Yaya Toure, David Silva and Sergio Aguero out of the blue (moon)? Perhaps the newfound Seriousness of Manchester City is entirely in line with the endearing silliness that the club has always possessed. Perhaps the inmates are still within the asylum, their chief delusion now their own sanity.

2 November 2011

Why Goals Aren't Overrated (But Javier Hernandez Is)

Players have positions. Over a century of crooked evolution has done nothing to dispute this. Certain positions have died, but the nominative principle remains. Indeed, it is so strong, that the most innovative players (Beckenbauer, Hidegkuti, and other sepia wonders) are awarded precisely their own positions, so that their revolutions might later be domesticated into the grey and essential world of categorisation. It is pointless to pretend that we can watch and appreciate football external to this gently shifting landscape of labels; labels that derive from those imaginary positions that make up formations (and Zonal Marking’s homepage), the places where each team’s players stand rooted semantically, if not literally, to the pitch.

Some players have the fortune and the misfortune to embody a position more totally than others. They smell of their position, of the very particular chemical needed to preserve the specimen. The catalogue of these archetypal players, if collated, would be the grand project of football classification, its Natural History Museum, or else a work of overarching and bizarre structural anthropology. When positions are this potently embodied, then we are dealing with the very foundations of the game, practically mythical, and we would do well to urge caution.

|

| Exhibition A: Last of the Inside Lefts |

Myths cast long psychological shadows, and the intimidation that can be achieved by the astute deployment of archetypes should never be underestimated. Perhaps no department of our Natural History Museum is as unnerving to the visitor as that which houses the archetypal, the indivisible goal-poachers. Lacking the liquid biceps and sideways swerve of a Van Persie, or the powerful idiosyncrasies of the crab-walking, childlike Ibrahimovic, these specimens are almost entirely defined by their dourness. No distinguishing features abound here, only slight physiological mishaps and unprepossessing haircuts. Yet how disturbing these men, under the blank museum lights! All they do is score goals: an act that is blank, apolitical, even acultural, and thus dangerous. Two examples should suffice. Gerd Müller’s first coach, the Yugoslavian funnybone Zlatko Cajkovski, quite rightly gave him the sobriquet ‘kleines dickes Müller’ – short fat Müller (even Cajkovski’s grammatically incorrect German seems apt for this stumpy, uneven little player). This small, hairy alcoholic was deceptively underwhelming that he would seem to enact a disappearing act on the field for long, precious minutes at a time. And then, from three or four yards, he would score, score, and score some more. Short fat Müller sacked arguably the greatest international team of all time when his odd body curled itself around an uninviting cross to make the scoreline West Germany 2 – 1 Netherlands in the 1974 World Cup Final; he nestles amongst a leper’s handful of the greatest strikers of all time, regardless of subspecies. And what of his modern, Mediterranean counterpart, Filippo Inzaghi? That lank hair, grey expression, offside gait and arrogantly devoid gaze he wears like an old cloak, beneath which he hides a dagger. Do we honestly think that the Fergusons, Guardiolas, and Mourinhos of this world are not afraid to see him standing on the touchline? They would be foolish not to be. This is precisely the point with archetypal players: they provoke justified fear, since they embody their singular role to the extent of near infallibility. We should fear the dour and the lumpen when they have scoring statistics like these.

We should not fear Javier Hernandez. At most, he should provoke faint annoyance, or the kind of half-amused pity that surfaces when we see a three-legged cat, or the fatigued motions of a water buffalo poisoned by ever-circling Komodo Dragons. He wants to have it all, to throw off the accumulative cultural weight of myth and boundary, whilst still being commended for the primitivism of his achievements. He is an anthropological short circuit. Hernandez is a goal-poacher, for sure: he is certainly no great passer of the ball, or crosser, or tackler, or trickster; he is quite fast and knocks it in from a few yards out. A valuable player, undoubtedly. But dour, that he will not consent to.

The Small Fat Pea’s chosen persona, rather, is one of ‘infectious enthusiasm’, ‘love of the game’; he is, we are told, a joyful player. He loved playing in the Mexican league but it’s even more exciting to play for a big team in a big league, and he’s so happy to play for Manchester United (look, he’s kissing the badge!), and if God lets him he’ll score loads and loads of goals against other big teams, and Wigan, and oh look it’s gone in off his pancreas wow wheeeeeeeeeeeeee. Javier is confused. His young and excitable self clearly loves football in the way a child loves the game; and yet his by-now-athletically-mature body is incapable of performing almost all the actions involved in an actual professional game. Thus he is become archetypal, adept at one alone. But the child-self protests (with a degree of petulance), and continues to enact that fabled infectiousness, apparently to the delight of fans who are perhaps guilty of indulging their own inner (footballing) child in their celebrations of his latest shoulder-dropping exploits.[1]

Perhaps the Pea’s anti-archetypal, anti-mythical quest for permanent joy is indicative of the globalisation and totalisation of the game. Permanent joy in the face of draining 1-0 away wins at Everton is of course an illusion, and yet the whole point of ‘infectious enthusiasm’ (indeed, all epidemics), is that they cannot be allowed to flicker; and this is particularly true when this enthusiasm is being used to market a product such as sport, whose unpredictability and fluctuating quality go against the solid principles of profiteering. The market resolves everything, even archetypes, into a two-dimensional version of itself, meaningless but valuable, and it allows Mr. Hernandez to accessorise his grim footballing job with cheeky Hispanic grins and endearing piety. In the same way, then, that the globalisation of football has meant the destruction of clubs’ regional identities and fan cultures, so it has removed something of the semantic coherence even of positions. Soon we may find ourselves living in a world not of trequartistas and left-backs, but simply of ‘top, top players’ – a world, coincidentally, where Jamie Redknapp would feel quite at home.[2]

|

| Nobel Pea Prize |

No doubt the perfectly accurate and scientifically justified observations above will be countered with claims as to PeaBot’s brilliant record as a player regardless of some pretentious nonsense about the superstructure of football’s mythical archetypes. Well, sure. And yet, let us not forget those moments when the Diminutive Vegetable’s limitations have been ruthlessly exposed, his enthusiasm shown to be a shield against the essentialised nature of his career, and I have been proven gloriously right. The Champions’ League Final of last season was a remarkable game, which played out like a series of rhetorical points being quite beautifully made. As Brian Phillips noted at the time, it is very rare indeed for a team to win as Barcelona did that night, entirely in their own way, with no aid from above or below, purely as an expression of the superiority of their performance of a reading of the game. In a sense, Barcelona are doing the market’s homogenising job on themselves, reducing their game to a series of rigid principles, and thus nihilistically maintaining an identity in the face of external pressure simply to exist in a frictionless, marketable manner. This is not a promising modus vivandi, but that night it clicked into a seamless performance. It is also rare for one player to be so completely at odds with the endeavours of the match around him as Mini Sprout was that day. He did nothing, except stand offside. For once, his childish sense of entitlement (to both goals and fun fun fun) wasn’t catered for, and instead he got to see what can happen when a team is fully at ease with its own identity and naturalist classification. Do people honestly think that Dimitar Berbatov would not have been more effective? Note: ‘effective’ is not the same as ‘enthusiastic’. Are we really so caught up in the hysterical merry-go-round of ‘infectious enthusiasm’ that we cannot accept that a languid, intelligent player, who is at peace with his languidness and intelligence and the impact these can have, would not have fared better on that strange, ideological evening?

[1] Young Master Pea’s structural deficiencies have short-wired the discourse of commentators, too. Caught up in the notion that this is joyful football, yet unable to square that with the dour actions Pea actually performs, we are told in breathless terms how skilfully he has ‘dropped his shoulder’, ‘stuck his leg out’, ‘folded his rectum’, and so forth.

[2] If this sounds rather unjustifiably dystopian, then I will say in my defence that I tried for ages to think of a ‘funny angle’ on the Señorita, but simply couldn’t: the little shit just isn’t funny.

13 October 2011

Kantona

The notion of football played

‘the right way’ is simultaneously a conceptual scourge to be fought, and an essential safeguard against the sundry Pulises of the world who fear nothing more

than beauty. How do we reconcile our need for some kind of aesthetic thrill

from matches with the fact that the nature of this thrill will remain ever

elusive? What too of those players (or, more rarely, teams) whose commitment to

the stylish overwhelms their connection to the brute ‘reality’ of the game? Put

more simply: what space does fantasy occupy in football?

For reasons that should become

more apparent later, this debate can be framed very neatly through a brief

consideration the notion of the good will in the work of the fusty

Konigsberger, Immanuel Kant. Kant bases his ethics upon the notion of the good

will – a will elicited in line with pure practical reason as opposed to

pathological motivations founded upon material practical reason. For example,

one must refrain from theft because this is the right thing to do, rather than

from fear of punishment; fear of the hangman’s noose does not make one a good

man, for otherwise all cowards would be men of great virtue. But how can Kant

prove that these non-pathological acts exist? The elusive quality that allows

pure reason to be practical (hence not pathological) – termed the

‘philosopher’s stone’ by Kant – is crucial to his philosophy. And yet the only

way that Kant can get out of this apparent dead end is to appeals to das Faktum der Vernunft (the fact of reason),

although he himself admits that no example

can be offered to support his argument: ‘the moral law is given as a fact of

pure reason of which we are a priori

conscious, and which is apodictically certain, though it be granted that in

experience no example of its exact fulfilment can be found.’[1] As

such we are left with a moral law which is simply a Faktum that cannot be demonstrated. What we have is a supposed basic fact and an apodictic appeal to a

conception of morality which is binding from that point on. Barcelona offer perhaps the closest

approximation to this in today’s game. The basic fact that they play

football in the ‘right way’ is undemonstrable, yet noted moralist Silvio

Berlusconi recently advised his Milan side to go out against Juventus and ‘play

more like Barcelona’. Proof if proof be need be.

In his essay Kant avec Sade, unbearable obfuscator Jacques Lacan pointed out

that the line of inquiry suggested by Kant opens onto far more expansive

vistas:

[T]he Sadean

bedroom is of the same stature as those places from which the schools of

ancient philosophy borrowed their names: Academy, Lyceum, and Stoa. Here as

there, one paves the way for science by rectifying one’s ethical position, in

this respect, Sade did indeed begin the groundwork that was to progress for a

hundred years in the depths of taste in order for Freud’s path to be passable.

If Freud was able to enunciate his

pleasure principle without even having to worry about indicating what

distinguishes it from the function of pleasure in traditional ethics…we can

only credit this to the insinuating rise in the nineteenth century of the theme

of “delight in evil”. Sade represents here the first step of a subversion of

which Kant…represents the turning point.[2]

For Lacan, Kant is not honest

enough to realise the full consequences of his philosophy and this honesty is

better seen in the work of Sade. Kant’s arrival at an aporia when attempting to discern the good will from a pathological

will means that he is forced to rely on a notion of conscience, a supposed

‘voice within’ which looks suspiciously like a slight of hand or deux ex machina. Sade entertains no such

fanciful optimism. Lacan identifies the following maxim for jouissance within Sade, noting that it

relates to Kant’s own maxim insofar as it is enunciated as a universal law: “I

have the right to enjoy your body,” anyone can say to me, “and I will exercise

this right without any limit to the capriciousness of the exactions I may wish

to satiate with your body.”[3]

This maxim appeals to the Other rather than the ‘voice within’. Given that we

cannot possibly discern the good will, it is the will to jouissance which more perfectly expresses freedom.

|

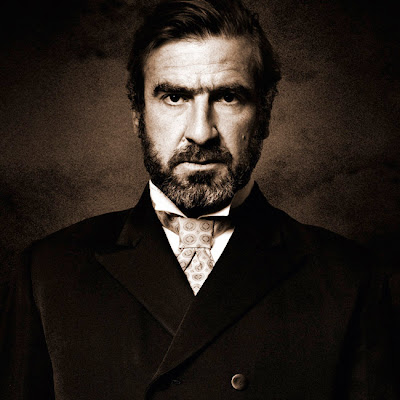

| "I'll put a fag in my mouth, and think of Sade" |

What then of footballing jouissance

and footballing good will? There are some who would claim that kung-fu

kicking a racist in the face is enough to elevate one above all future

criticism. For the duration of this piece, let’s pretend that I think

otherwise. Of course I am talking about Eric Cantona, a man habitually regarded

as the catalyst for Manchester United’s ascent towards the summit of world

football and one of the greatest players ever to have played in the Premier

League. But this is not what interests me about Cantona: whether Manchester

United sink or swim in the top flight is not really my interest. What is of

more interest is what Cantona brought out in the fans who so admired him,

rekindling a certain hope and bringing to the fore an appreciation of art in

addition to the artisan.

Cantona has a place in an

impressive lineage of Manchester United number 7s that also includes George

Best, Bryan Robson, David Beckham, Cristiano Rolando and @themichaelowen. All

of these rank amongst the best players in the history of the club (apart from

Owen), and all of them were winners (again apart from Owen). But Cantona

brought out something else in supporters. He was acknowledged as a winner, but

above this, he was recognised as an artist. For a striker, his record of 64

league goals in 143 games for Manchester United is hardly exceptional. The

starkest contrast is with his contemporary successor, Cristiano Ronaldo. CR7 is

a machine of a player, a statistic on steroids heading in locomotive fashion

towards success via the shortest, most economical route possible. Cantona was

not like that. Trailed by the seductive aroma of Gallic nonchalance, Eric

always seemed as if he was only partially focused on the win – he had other

considerations to pay heed to. Indeed Coupe du Monde winning coach Aime Jacquet

once said of Cantona: ‘Sometimes he lacks the killer instinct in front of goal.

There he is a poet, in love with the ball, seeking a gesture for its own sake.’

A criticism and a compliment in one, this encapsulates Cantona perfectly: a

great player, yes, but perhaps one too in love with what he perceives to be

beautiful to deliver the ugly, killing blow (the ‘Dirk Kuyt’, to coin a

phrase).

The conventional narrative, then,

might have us consider Cantona as something of a poet, if we take poetry to be

symbolic of decoration and artifice. Through poetry he escaped the idea of football

as solely orientated towards the win. It is a nice thought, but we could easily

look at this from another, less charitable angle. What if, rather than seeing

Cantona as endorsing art for art’s sake, we saw his perceived charity as a

handy deflection for a surplus of ego? Was the unnecessary pass to the teammate

an act of gratuitous good will or just an attempt to show how good he himself was?

Were Cantona’s acts those of egomania or florid poetry? In order to address

this question, it is useful to refer back to elucidate the role of fantasy in

ethics through the dynamic between Kant and Sade.

|

| Immanuel Kantona |

We have seen how by breaking down

the conventional dialectic between desire and Law – arguably reducing them to

one and the same thing – Kant clears the way for Sade. But I do not believe

that it is a failing of Kant to not go so far as to adopt a Sadean outlook. The

explanation for the difference in their respective philosophies can be

explained with reference to the respective fantasies invoked by Kant and Sade. In

both Kant and Sade an apparently indifferent nature is supplemented by a

second, ethical, nature: in Kant the kingdom of ends and in Sade the pursuit of

evil. The fact that their ethical edifices are supported by fantasy certainly

affects how they should be read.

In the work of Sade, enjoyment is

inhibited by the pleasure principle (the limit to what the body can endure)

since the body is not designed to go the full lengths of enjoyment such that

desire can be properly fulfilled. What Sade proposes is a fantasy of infinite

suffering, a suffering which can surpass the physical limits of the human body

in order to journey further still towards satisfying desire, even though that

desire will never be fully satisfied. The promise of eternal torture is the

fantasy which sustains the Sadean anti-ethical edifice. But there is an equal

and opposite movement within Kant’s ethical edifice, as Alenka Zupančič has

noted:

‘For Kant,

freedom is always susceptible to limitation, either by pleasure…or by the death

of the subject. What allows us to ‘jump over’ this hindrance, to continue to be

free beyond it, is what Lacan calls the fantasy. Kant’s postulate of the

immortality of the soul…implies precisely a fantasmatic ‘solution’… [I]f you

persist in following the categorical imperative, regardless of all pains and

tortures that may occur along the way, you may finally be granted the

possibility of ridding yourself even of the pleasure and pride that you took in

the sacrifice itself; thus you will finally reach you goal. Kant’s immortality

of the soul promises us then quite a peculiar heaven. For what awaits his

ethical subjects is a heavenly future that bears an uncanny resemblance to a

Sadean boudoir.’[4]

In short, Kantian ethics includes

the possibility of anti-ethics but for the thin veil of fantasy. Yet whilst Kant’s

fantasy at least aspires towards some idea of a good, Sade’s fantasy is one of

selfish depravity, blind to the notion of the good will and non-pathological

acts.

Returning to Cantona, then, we

can see the terms on which fans can interpret him as eliciting art for art’s

sake as opposed to indulging his own ego – or, exaggeratedly, why he is seen as

residing in the kingdom of ends as opposed to the Sadean boudoir. It must be

their fantasy that there is inherent value in aspiring towards the beautiful.

Within the framework discussed above, this is how we can distinguish Cantona’s

work from Sadean self-indulgence. That fans were willing to read Cantona as a

poet as opposed to an egomaniac speaks of the concealed poets within all

football fans who, whether or not they can enunciate it themselves, have an

idea of what they find admirable and desirable in the game, irrespective of the

result at the end of ninety minutes.

Of course this is only binding if

one accepts a rigidly Kantian/modern framework. Personally I would question

whether the mere fact that one enjoys something detracts at all from whether an

action is good or not. Here, perhaps, we would do well to consider Dennis

Bergkamp, a player who, like Cantona, was accused throughout his career of

lacking a killer streak. Bergkamp was not always looking to score: ‘I was

looking for that pass all the time, and the pleasure I got! It gave me so much

pleasure, like solving a puzzle. Scoring a goal is, of course, up there. It is

known. It’s like nothing else. But for me, in the end, giving the assist got

closer and closer to that feeling.’[5]

Cantona is more than a player,

for he is also a figure of fantasy. The way that he is remembered by football

fans speaks of the hope that poetry can shatter the prosaic, the pathological

and the mechanic; the hope that art can overcome ego. It is interesting how we

are unwilling to read others in the same way: Ballotelli’s insouciant back heel,

for example, was not considered art but rather petulance. Perhaps nowadays,

with a high quality domestic league and global televised football, we are no

longer looking for Eric (like the film!) to provide this reassurance. It is

telling that in France Cantona was regarded variously as ‘a pretentious country

boy, a roughish son of Marseilles, an idiot

savant.’[6] Who is

to say that if he walked amongst us today he would not be derided (much like

Plato’s returning escapee from the cave)? Somewhere in Cheshire, Dimitar

Berbatov sits alone, his retina burnt by the sun, wondering what would have

been if only his fans had fostered more fantasy.

|

| Burnt by the sun |

[1] Kant, Immanuel (2004) Critique of Practical Reason, Kingsmill Abbott, Thomas (trans.),

New York, Dover Publications, p.48.

[2] Jacques Lacan, ‘Kant With Sade’, in Ecrits The First Complete Edition in English,

trans. Bruce Fink (New York:

W. W. Norton & Company, 2006), p. 645.

[3]

Ibid, p.648.

[4] Alenka

Zupančič, ‘Kant with Don Juan and Sade’, in Joan Copjec (ed.), Radical Evil (London: Verso, 1996), pp. 120-121.

[5] For more

gems like this see David Winner’s

interview with Bergkamp in episode 1 of The

Blizzard.

[6] Ian

Ridley, ‘‘Oooh, Aaah, Cantona!’’, in Christov Ruhn (ed.), Le Foot (London: Abacus, 2000), p. 155.

1 October 2011

Love and Death and Football

Let’s start from the

consideration that each game of football can be understood in terms of a story

constructed over 90 minutes. The manner in which any given game is played

determines the content of this story, establishing the horizons of possibility

onto which the narrative opens. This is an uncontroversial opening gambit. Now

stories that are constructed do not just happen

– rather they have authors who construct the narratives, shaping the direction

that the tale will take. What I would like to consider, ever so briefly, is the

concept of authorship in conjunction with narrative in football. There’ll also

be some stuff on Juan Roman Riquelme, prostitutes and Jesus (stay with me

here).

The first thing that needs to be

established is who, in reference to football, the author is. It could be argued

that the fans or the media constitute the author, insofar as they construct the

main narratives that haunt the back pages of the British papers on a daily

basis – the kind of nonsense narratives like Roberto Martinez being a good

manager, etc. Now this is certainly a kind of authorship, but it is limited to

our perceptions of the game, not the game itself – whilst the press may provide

us with a lens to view the game, they cannot actually play out the games. As such

we can discard these budding authors from this discussion. Of more interest

will be the manager and the players. Both of these can be seen as being

directly responsible for the authorship of the game: the manager by picking the

team and setting their philosophy and the players by literally playing the

game.[1]

So if manager and players are

authors of football, what then? What I would like to suggest is that different managers

and players are representative of different conceptions of authorship, and hence

of different narratives and styles of football. In the broadest sense I will

distinguish between positive and negative narratives and consider these through

two figures (both GULag favourites): Fyodor Dostoevsky and Woody Allen.

|

| Faves |

Dostoevsky and Allen have very

different ideas of authorship. Dostoevsky’s notion of authorship is best

understood as the provision of time and space for characters to develop within

the context of the narrative.[2] This

developmental space means that there can be no arbitrary last words in the

narrative; it is crucial that all beliefs held are challenged within the

context of dialogue, which refuses a last word – there are no lapidary

statements providing closure. For example, Alyosha Karamazov is not simply a

holy fool – there are points where he expresses doubt with regards to his

belief. The refusal of the closure provided by a last word there is accompanied

by a measure of openness suggested by the possibility of free acts. The most

famous example of this might be within Ivan’s story of the Grand Inquisitor: after

the Inquisitor’s long speech Christ responds simply with a kiss. This, of

course, is echoed by Alyosha, who, when similarly challenged by Ivan, repeats

Christ’s gesture. Alyosha’s gesture, like that of Christ, is a gratuitous act

of compassion in response to hostility. Whilst we cannot rule out all

pathological motivations for this act, perhaps we can read it as showing that

there is the real possibility for free and compassionate response in an

imperfect world. What the Dostoevskian notion of authorship holds to be

important, then, is the free agent who is not constrained by arbitrary last

words. This does not lead to the arbitrariness of actions, however; Dostoevsky

does not deny that there is a good, merely the precariousness of our

relationship to it. But at least through the freedom that agents possess they

are able to work out how they might aspire towards an ethical form of life. This

is an incredibly brief summary of a very interesting area, but it does give an

idea of what authorship is for Dostoevsky: the provision of time and space in

which possibilities can be enacted that can lead to real (moral) growth.

I would suggest that the

Dostoevskian idea of authorship is similar to the authorship borne witness to

in teams with a more positive style of play. It gestures towards an open,

creative game. Rather than possibilities being restricted, they increase

exponentially – the team probes and asks questions, both of itself and its

opposite, in search of novelty and wit. As a microcosm of this notion, consider

the classic number 10 as a Dostoevsky-style author, providing time and space

for the flourishing of creativity. Indeed in a previous post we have already

considered the playmaker as a creator in a similar respect. The perfect pass can change the dynamics of

the game, allowing teammates to escape markers and dash into unoccupied areas

of the pitch. This is the romance of the number 10 – he is an avatar for

creativity, embodying the most positive aspects of the game.

Allen, however, has a far more

negative idea of the author. This is seen in films such as Hannah and Her Sisters, but best in the utterly unapologetic Deconstructing Harry. Here Allen plays

the apparently unredeemable Harry Block, an author who has destroyed almost all of his real life relationships, living

from whore to whore, only able to function within the fictions that he creates.

The work that Block authors is entirely parasitic upon his life and the lives

of those around him. There is no real innovation or novelty, merely the

recycling of the old. Everything has already been done in one way or another

and everything going forward will have been adumbrated and prefigured. There is

something vampiric about the author in Allen’s work – he is of the same

genealogy as the pervert and the scrapbooker. In contrast to Dostoevsky,

Allen’s idea of authorship is about the closure and destruction of

possibilities and approaches innovation with suspicion and weariness. Perhaps this

is why Allen’s more recent efforts have come across as little more than

inferior copies of his earlier works (consider Match Point and Crimes and

Misdemeanours, for example). Even in his most accomplished films, haggard

tropes abound, of the benefits of sleeping with children in Manhattan, e.g..

I would suggest that the author

in Allen’s work is reminiscent of the ethos behind a more negative approach to

football. Consider those coaches for whom every situation is reducible to a

drill that can be repeated ad nauseum

on the training field, for whom rehearsed set plays are both the substance and

limits of the game. Basically, consider Sam Allardyce. For this breed of author

within football there is no room for genuinely creative and innovative players

– they are too undisciplined to work within the constraints imposed upon them

and too inconsistent to provide for the team over the duration of a game. For

this author, it is better to rely on statistically backed sources of

chance-generation: set pieces and moves with as few complications (or passes –

perhaps it is damning that this type of author might equate ‘passing’ with

‘complication’) as possible.

In the history of football

clashes between the ‘Dostoevskian’ football and ‘Allenic’ football have been frequent,

perhaps primeval. Maybe the most entrenched opposition would be in Argentina,

where the division between Menottistas

and Bilardistas provides two clearly

defined camps. Menotti’s teams played wonderful attacking football that also

got results. Bilardo, in contrast, was schooled in the Estudiantes de la Plata

side of Osvaldo Zubeldia, a notoriously cynical team who achieved Libertadores

success in the late 60s playing what would be dubbed anti-futbol. Whilst it is not entirely straightforward, we could

well understand Menotti as a Dostoevskian author and Bilardo (or, for that

matter, Zubeldia) as an Allenic author.

What is important to stress is

that these are both just attitudes. On an ontological level the Dostoevskian

author does not actually ‘create’ space – he merely approaches time and space

in a manner conducive to creative ends; the playmaker does not create time and

space – the pitch is finite – he merely interprets the space in such a way as

to allow spontaneous expression. Likewise Allen does not reduce actual

possibilities, but the repetition and derivation that we see in his work is suggests

the finitude of possibility. The two ways of thinking essentially look at the

same thing from two angles – perhaps the world is neither as open as Dostoevsky

would suggest nor as closed as Allen would suggest. It is reducible, in a way,

to whether one is an optimist or a pessimist. Perhaps, as Allen suggests, we

should take the pragmatists’ route and go with ‘Whatever Works’. Of course,

Dostoevsky rejects this fairly explicitly in Brothers Karamazov (where the notion that anything is permissible

in the absence of God is ultimately rejected). Maybe it’s as simple as asking:

what kind of story do we want to tell? What kind of story do we want to see

told?

This is why players like Riquelme,

who constantly creates space and time for other players through his passing,

are thrilling. What is gorgeous about Riquelme is the impact he has upon the

pitch. Potential is everywhere and you are unsure as to where the danger will

come from next. The killing pass, a traumatic event for the opposition, fools

everyone, just as how, in an open narrative, the readers are carried away with

the twists and turns of the plot.

|

| We call upon the author to explain |

I am not saying that the only way

to play is like Riquelme and the only way for managers to think is like Menotti.

Obviously it is important to incorporate creativity in a team that also has a

sense of industry and, depending on your playing staff, you may have to tailor

the degree of industry to their ability of your playmakers. For instance, if

your playmaker is Jermaine Pennant then your players will have far more to make

up for through physicality than if it is Mesut Ozil. What I would say, however,

is that there is a positivity, an optimism, about allowing this belief in the

potential for creation and spontaneity, that I feel is very important in

football. We may not always notice when it is there, but its absence is keenly

felt and, as a keen reader, it is something that is always greatly missed.

[1] Of

course Steve Bruce is literally an author, having penned such works as Sweeper!, Defender! and Striker!

Unfortunately these artefacts will not be considered in this piece.

[2] This

reading of Dostoevsky derives from recent work by Rowan Williams. See Rowan

Williams, Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and

Fiction (London: Continuum, 2008).

25 September 2011

Fear and Trembling

Tony Pulis wears a baseball cap.

He is also terrified.

Upon promotion Stoke practised a

style of football which relied heavily on physicality and set pieces. Rory

Delap’s long throw was one of the main themes of their debut season in the top

flight (in fact only recently did I learn that Delap was a midfielder – I had

always assumed that his preferred position was a few steps back from the

by-line). Pulis was quick to acknowledge Stoke’s prosaic play and to insist

that upon establishing them in the division his aim would be to make the team

more aesthetically pleasing.

|

| Dr Frankenstein |

Now we are a few years on and it

cannot be denied that on the pitch Stoke have been successful – a decent league

position in 2010-11 and reaching the final of the FA Cup (and hence the Europa

League) marked another step forward for Pulis’ team. It is also true that last

season Stoke got amongst the lowest number of goals scored from open play in

the Premier League. This is not a bad thing: they were joined there by high scorers Man City and Newcastle. Clearly the directness of their play is not a problem in terms of success – is

it any wonder that Pulis has not changed their style, as promised?

The GULag is not a football snob.

Not all teams have to play like the best clubs in Europe (Barcelona and Wigan)

to draw praise. What I want to know is: why did Pulis even feel the need to

make this promise? I don’t mind direct football. It is actually very

entertaining – far more so than a soporific game based around possession and simple passes. Good direct football can be both entertaining and successful – some clubs have

built their identity around this premise, such as Athletic Bilbao. I feel that

Pulis’ broken promise really shows that deep down he actually holds these

prejudices about football: the Premier League’s most notable exponent of direct

football actually looks down upon it. We can contrast this view with that of

Mick McCarthy, who unashamedly plays direct football in an entertaining manner

(and even Roberto Martinez, who plays indirect football in an unentertaining

and unsuccessful manner).

The problem with the football

that Stoke play is not the style, but rather the spirit. Direct football does

not need to be violent or cynical and mental toughness needn’t break legs. Last

season there was a furore concerning tackles and Stoke and Wolves were at the

centre. After Jordi Gomez was injured in a terrible tackle by Karl Henry, Mick

McCarthy conceded that his players needed to calm down. Pulis, after similar

incidents, was more likely to appeal to that well-worn refrain: “He’s not that

kind of player.” Danny Murphy made a good point when he noted that managers who

worked players up too much before matches were more likely to see those players

make reckless tackles. The point that I am making is simply that the way Stoke

sometimes like to imagine themselves playing, a tempering of directness with

exaggerated muscularity, can be very dangerous.[1]

|

| Frankenstein's monster |

So why do Stoke play this way if

Pulis views the football played by Stoke as inferior? The answer is simple: he

has created a monster on the back of his success and to tamper with the formula

is too risky. He is an addict! Flair signings such as Tuncay and Gudjohnsson

didn’t work out; only more functional wingers, Etherington and Pennant (the

latter having damningly attracted the eye of Rafa Benitez), stood a chance.

Unable to change Stoke’s style, Pulis can only make it more pronounced. Stoke

are evolving, but into what? The direction that this evolution will take is in

Pulis’ hands. He could follow through on his promise to make Stoke a side full

of diminutive passers, but this is neither likely nor necessarily favourable.

In terms of developing the style of play that Stoke prefer he can make it a

better form of direct football or a more violent form of direct football. In

the meantime, Pulis will continue to work out his salvation with fear and

trembling.

[1]

This applies to the self indulgently primeval contingent amongst Stoke's fans, too. One senses that,

psychoanalytically speaking, they are attempting to hide the ugliness of their

affections in plain sight, by booing Aaron Ramsey’s splintered leg, for

instance.

4 September 2011

The Deathly Dance of Joseph John Cole

The hour was late when the window slammed shut. After flurry of late activity, followed by the slow trickle of further mundane revelations, the GULag acclimatised itself to the fact that the 2011 summer transfer period was over. Chancy penny-pinchers Everton managed to avoid spending any money for what seems like the eighth year in a row; Newcastle would not sign the striker they so dearly needed; Kenny Dalglish managed to offload a pesky foreigner. Perhaps these movements were predictable, but some onlookers expressed surprise, dear reader, that Joe Cole had left these shores to ply his trade with French champions Lille. Well, surprise to some, perhaps, but not, I must insist, to Nineteenth Century symbolist painter Felicien Rops – the fantastically moustached Belgian whose uncanny prescience on this matter should arouse suspicions of spiritualism and dabbling with the occult.

In his work, Death at the Ball, Rops presents the image of death as a grim skeleton, posturing seductively in a ball gown. I would challenge anyone to look upon this image and not be immediately put in mind of Joe Cole. Cole, a product of West Ham’s famous youth academy (sic), was vaunted as being one the most naturally gifted footballers ever produced in England. He was, according to those who we would give the appellation ‘experts’, destined for big things. From West Ham he went on to play for Chelsea and Liverpool before his move to Lille, as well as making over fifty appearances for the national team. Indeed the qualities that marked Cole out as being special are not lost on Rops. Consider the elegant woman’s foot which coquettishly protrudes from the hem of the gown in the aforementioned painting – Joe always was dainty on his feet. Yet his gentle grace on the pitch has always counted against him somewhat, as if he was not quite muscular enough to play in the English game. Cole, like the skeleton figure of Death, is lacking meat on his bones.

|

| Portrait of a midfielder? |

It is because of this perception of his weakness that Cole's career has not been flush with success. He has often been sidelined at clubs and rarely played in his favoured position. In the painting this is suggested by the ominous darkness that surrounds the dancing spectre.[1] Indeed the general juxtaposition between vitality and morbidity seen in the form of Death is reminiscent of the tension between Cole’s undoubted talent and his often underwhelming impact. Rops confronts us with the image of a skeleton dancing long after the dancing should have stopped, with the death of the body. Has Cole continued to dance when he should have stopped long ago? Is there not something undead about his career? And has it taken our long deceased painter-seer to draw our attention to this?

In the darkness behind Death we can just about see a figure lurking, almost entirely consumed within the black. Who is this figure? One cannot help but jump to the obvious conclusion: Harry Redknapp in mischievous disguise. But what is his intention? Either way, it is clear that Cole’s future rests here, in the shadows, subsumed in uncertainty. In this work, Rops provides us with a tension between death and sexuality that perfectly captures Cole’s enigmatic position. As much as a sense of disappointment will always be attached to Cole and his faltering career, he retains the vague air of the sexy continental passer-playmaker that he had the potential to be. Rops was correct: Cole may be little more than a shade, but he is certainly a seductive one.

[1] In reference to the colour pallet used, note also that the ball gown is made up of Lille’s colours. Did Rops know? We must conclude that he did.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)